Inverse Intuition > Intro to Humanities > Formalism

Formalism

"Due" by Sept 28th

Purpose: To analyze, think, and write in a Formalist style of discussing art.

Directions

Example art pieces

- Find a painting that 1) is in a museum and 2) was made in or after 2018.

- If you choose a minimalist painting like this and cannot write about the 6 elements of formalism, you'll have to choose a different painting.

- Save the link to the web page on which you found the painting as you'll need to put that link with the assignment

- You will be applying 6 elements of formalism to the painting you find: Line, Shape, Value, Texture, Color, and Space.

- Use either word or powerpoint.

- Give a title page to your word doc or powerpoint

- On the next page put the image of the painting including artist name, year, title of the piece and which museum the art is in as well as the web address to that painting.

- The third page will be blank for now; you'll call it summary and summarize your findings after you go through all 6 elements.

- After those three pages, discuss one element per page.

- State the element as a subhead to the page

- Use lines/circles/boxes, or other shapes to digitally draw on the painting as per the examples below

- Inset a text box to discuss each element in relation to the painting.

- Lastly, return to page three and connect all the various elements (as discussed father below in the conclusion, but this "conclusion" must be on YOUR third page. )

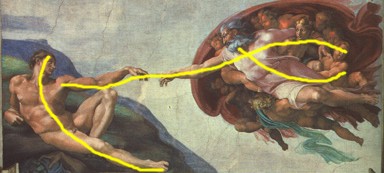

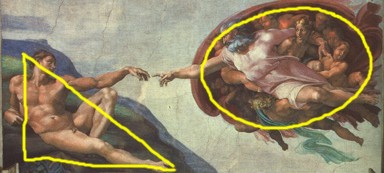

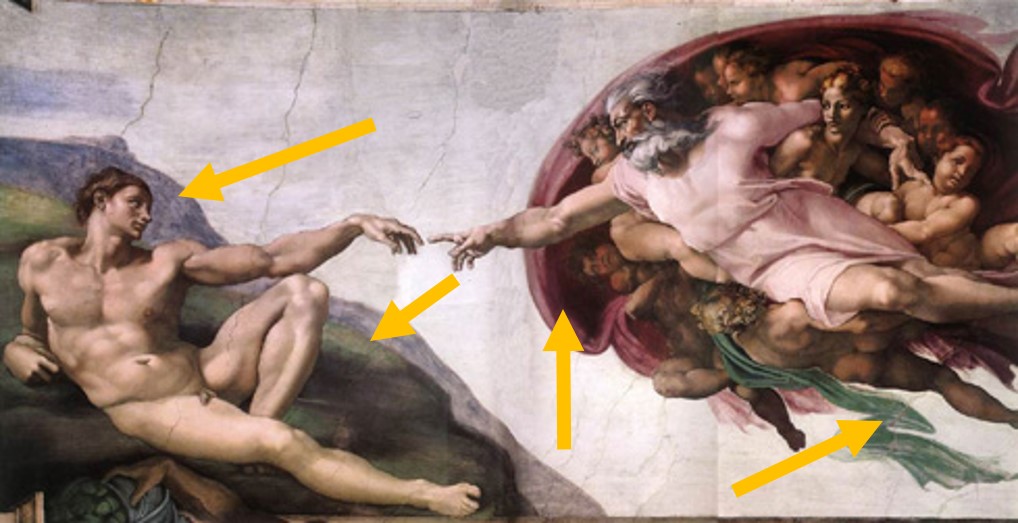

Michelangelo. The Creation of Adam. 1508-1512. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican.

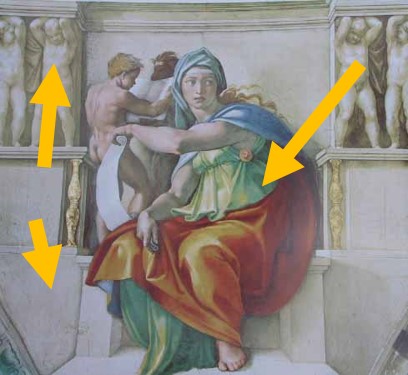

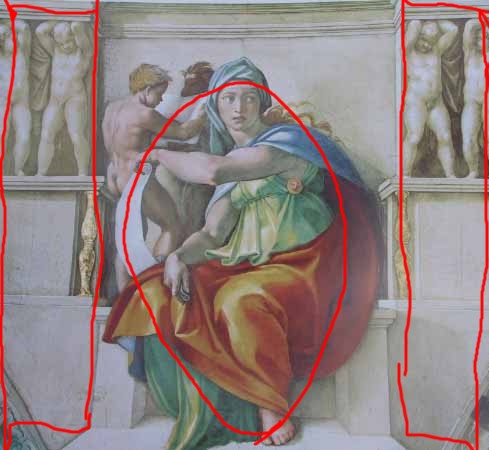

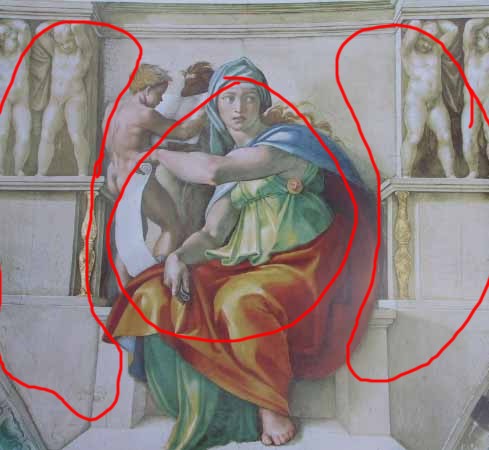

Michelangelo. Delphic Sibyl. circa 1500. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican.

Description of Elements and Examples

The Aim of this assignment

- To discuss and arrive at an analytical discussion of a painting by using Formal critique

- Keep in mind that this is not merely an exercise of applying the Formalism to painting; it's a manner of deriving an abstract concept that a painting espouses.

1. Line

What is it?

- A line is defined as a mark with length and direction, created by a point that moves across a surface.

- Lines can be three dimensional, two dimensional, or implied.

- With three-dimensional, the line is an actual protruding piece of the art, such as a statue holding out a spear. We won;t be using three dimensional lines for this exercise.

- With two-dimensional, the line is an actual drawn line on paper (or other surface). We most likely won't be using two dimensional lines for this exercise.

- With implied, the line is the movement of the eye across the piece.

- We will be looking for implied lines.

- Lines can curve, twist, or run in a straight line. Sometimes there is one main line and then smaller lines. Sometimes there are many lines and one main line is not apparent.

- In the painting below, notice how these lines intersect, split, or move in different directions.

- A line is the line made by our eyes when we look at a piece. It's not just a physical line; it's the "line of sight of you, the viewer."

- You will have to be able to draw the lines on the image (seen below) as well as write about those lines.

How to discuss lines in art: Creation of AdamIn The Creation of Adam, Adam's line (his body) is curved like the letter c (or like the Nike symbol). That is, our eyes follow from his head and down his body to his toes. Another line is begins at Adam's shoulder, crosses to God's arm, continues along God's chest, and along God's other arm into the eyes of the "woman/angel."

Some interesting notes on these lines:

- Adam's lines cause tension

- They cause tension because our eyes want to go into two directions, one to follow his body to the feet and the other to go along the arm and to God.

- God has two lines, his arm and his body, but both sweep into and end at the far right cherub, which does not cause as much tension as with Adam's split lines.

- With Adam, the lines make his side of the picture "busy," meaning we become "busy" on that side figuring our where our eyes want to go.

- However, the lines on God's side are more easy on the eye, and cause less dissonance.

How to discuss lines in art: Delphic SybilIn Delphic Sybil, there are also two major lines: one line is the curve of her body, the other line runs along a platform along her arm and along the other platform. Here this curving line and the horizontal line cause tension; the eye wants to follow the curve of the body, but it also wants to go along the horizontal.

2. Shape

What is it?

- A flat figure created when actual or implied lines meet to surround a space.

- A change in color or shading can define a shape.

- Shapes can be divided into several types: geometric (square, triangle, circle) and organic (irregular in outline).

- To see shapes, de-focus from the "action" and look at parts of the picture. Sometimes it helps to squint or look at the piece from a distance, thus removing the clarity of individual people or objects.

- You will have to be able to draw the shapes on the image (seen below) as well as write about those shapes.

How to discuss shapes in art: Creation of AdamThere are two major shapes in The Creation of Adam. Adam's background is, in this picture, pretty much triangular, and God and the host's shape is oval.

How to discuss shapes in art: Delphic SybilThere are three major shapes in Delphic Sybil. Her body is a vertical oval (the parchment she holds creates the left side of the oval). To her left and right is the second and third shapes, which are identical, long, vertical rectangles.

3. Value

What is it?

- Value is often the single most important element in paintings and drawings that allow us to see forms.

- In other words, value and the differing allow us to see not just shapes, but depth.

Range of Values

- You will have to be able to draw areas on the image (seen below) to show the value areas as well as write about those values.

How to discuss value in art: Creation of AdamThere is little to no value in the "sky" in The Creation of Adam; it is a flat surface. However, we can see greater value in the cloth around God; a deep shadow in the cloak makes it look like it has depth.

How to discuss value in art: Delphic SybilThere is not much value in the background of Delphic Sybil, but her robe has a deep shadow, an increased value. The other shadows seem to lend an increased value, but overall the piece looks flat.

4. Texture

What is it?

- The way a surface feels if it were real and we could touch it(actual texture ) or how it may look (implied texture).

- Texture can be sensed by touch and sight.

- Textures are described by word such as rough, silky, pebbly, spiky, soft, prickly, slimy, and sticky, etc.

- When analyzing texture, attempt to differentiate between the actual painting and any weathering or ageing. With older pieces, the paint can crack.

- In The Creation of Adam, we can see cracks, but this is the wall.

- To comment on those cracks as texture is to comment on the wall (which we are not doing); we should comment on the artistic ability put into the piece.

- While one form of texture analysis is discussing the actual topography of the paint on the canvas (such as thickness of paint), we are using a secondary formalist use of the word "texture": illusionary texture

- Illusionary texture is what something might feel like by how it looks.

- Think about how objects in your examples would feel if you could touch them in reality.

- A good example of multiple textures is Charles V with a Dog.

- The fur of the dog (soft), the more fluffy fur of Charles' rope (very soft and comfy), the wicker looking substance that is supposed to be his leggings on the upper thighs (rough), the stringy soft tassels of the object he holds (silky), the cottony look to his stockings (smooth), and the rigid solid look of his "shirt"(smooth and hard).

How to discuss texture in art: The Creation of AdamIn The Creation of Adam, God is surrounded in smooth, soft people and fabric. Adam is smooth, but sits on hard ground.

How to discuss texture in art: Delphic SybilIn Delphic Sybil, she is smooth and her surroundings are soft, the cherub statues in the back looks smooth yet hard.

5. Color

What is it?

- The perceived character of a surface according to the wavelength of light reflected from it.

- Color has three dimensions:

- Hue : indicated by its name such Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet

- Value (its lightness or darkness; see Value, above)

- Intensity (its relative purity or saturation; relative, here, means that the color compared to colors near it can make the color appear deeper.

- For instance the same yellow color looks less intense next to white, but it looks more intense next to black)

- Hue is the shade of a color; intensity is a relationship of a color to other colors; value is light and dark relationships.

How to discuss color in art: The Creation of AdamIn The Creation of Adam, in the green scarf (underneath God), we can see a changing of values in the green color, from a light green to the darker green of the folds of the scarf. The intensity of the green is more vibrant since it is nearly encircled in the larger red cloth. The red color intensifies the green color.

How to discuss color in art: Delphic Sybil

In Delphic Sybilthe simple off-white background color accentuates and intensifies the deep reds and blues of the main figure. The hues in both robes are deep reds, almost burgundy, and the blues are light and almost pastel.

6. Space

What is it?How to discuss space in art: The Creation of Adam

- The empty or open area between, around, above, below, or within objects.

- Shapes and forms are made by the space around and within them.

- Space is often called three-dimensional or two dimensional.

- Positive space is filled by a shape or form.

- Negative space surrounds a shape or form.

In The Creation of Adam there are two positive spaces, and a negative space between them.

How to discuss space in art:Delphic SybilIn Delphic Sybil, there is one positive space and two negative spaces (on either side of the positive space).

Conclusion

What is it?How to write-up the whole assignment:

- For page three, the summary, you need to connect all of the elements together.

- Don't just copy what you said above for the conclusion; connect the different aspects together.

- In the conclusion, no element should be discussed on its own.

- Sometimes you can connect all of the elements; sometimes you will have to bunch the elements in small groups.

- Below, the bracketed words are meant to show you where I use each aspect in the conclusion.

- You must use these brackets in your conclusion as a means of telling me you have covered each of the elements

Tension between the main figures and other figures informs both The Creation of Adam and Delphic Sybil. The line [line] of the figures in both pieces draw the reader from positive spaces into negative spaces [space]. We don't want to be in those dull colored [color] negative spaces that are low in value [value], and we retreat to the high value, vibrantly colored, soft, smooth feel [texture] of the figures in their geometric pleasing shapes [shape] (unlike the non-geometry of the negative space). But, once we are safe in those spaces, the lines drag us back out to the negative spaces, and the tension goes on and on.

Some notes on creating a conclusion

- Tension is not the only theme. (Tension, by the way, is not nervous anxiety or strife between the characters in the painting.)

- Tension, here, is merely the pulling of the eye and mind in many directions due to the formal elements.

- In The Death of Socrates, below, tension is quite evident as a human emotion, but you would have to show how the Formalist elements cause tension.

- (Again, do not interpret the theme of the painting's or sculpture's story as "tension"; argue your theme by using the formalist elements.)

Jacques-Louis David. The Death of Socrates. 1787. Oil on Canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York.

- Sometimes you could claim tension is evident, but the main "theme" you derive from two pieces might be something like movement, such as in the two pieces below.

- In the Pieta (left-side image) the figures have an intense sense of movement. If alive, the next seconds can occur in many ways: from a collapsing of all of the figures to a raising up of the central figure of Christ.

- David (right-side image) is static, frozen for eternity.

- If alive, the next seconds of David's life would still be standing there looking away

- There is no movement in David; there is lots of movement in Pieta.

Michelangelo's Pieta and David